Creating New Quantum Materials, Atom by Atom

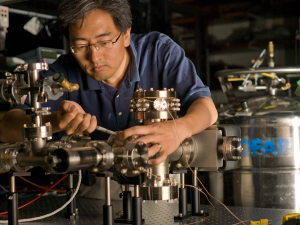

Visit physicist Divine Kumah in his research lab and you’ll find him making what could be described as the world’s tiniest layer cakes.

How tiny? Try just a few atoms thick. One hundred thousand of them would barely stack up against a sheet of paper. They’re not for eating, however. He takes his ingredients from the periodic table — oxygen and different metals such as titanium and magnesium — and brings them together in ways not found in nature to create ultra-thin films, one layer of atoms at a time.

For Kumah, who joins the Department of Physics this year as an associate professor, it’s in the areas where the different layers touch that things get interesting.

Kumah studies the physics at play in these interfaces: how their atoms shift, how electrons move through them or orient themselves, what happens when you heat them up or subject them to stress and strain.

The answers will help him design the next generation of materials for a wide range of applications, from memory storage to sensing to quantum computing. He imagines computers that operate at the level of single atoms. Ultrafast processors and sensors that generate little to no waste heat. Electronic circuits that imitate the neurons in the brain.

“Most materials change how they behave when you make them really, really small,” Kumah said. “It sounds like magic, but then we try to understand why it happens.”

Kumah’s interests in materials and how they tick surfaced early.

“I remember as a child in elementary school, going into my mom's room and mixing different things together,” Kumah said. “Nothing dangerous, but perfumes, anything at all.”

Kumah grew up in the West African port city of Accra, in Ghana. There, the electricity supply relied heavily on a hydroelectric dam, and his family would often lose power during the dry season or whenever water levels fell too low.

“That got me interested in trying to think of materials for solar panels,” which rely on semiconductors to convert sunlight into electricity. “I've been really fascinated with materials since then,” Kumah said.

His last year of high school, he spent a semester in El Paso, Texas, as an exchange student through the nonprofit Youth For Understanding. When he went back home he had every intention of staying in Ghana for college. “I was thinking of studying engineering,” Kumah said.

But then he was offered a fellowship to study physics at Southern University and A&M College in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He had extended family nearby, so he decided to give it a go.

Kumah received his B.S in physics from Southern University in 2004, and went on to earn a Ph.D. in applied physics from the University of Michigan in 2009.

He did postdoctoral research at Yale University and then joined the faculty at North Carolina State University in 2015, where he rose through the ranks to Associate Professor of Physics before coming 25 miles to Duke.

Kumah studies what’s known as condensed matter physics, a field that concerns itself with how atoms — the building blocks of matter — are arranged and how they interact.

It takes millions of atoms to make a speck of dust. To image materials at this tiny scale, Kumah uses intense X-ray beams at the Argonne National Laboratory outside Chicago to pinpoint exactly where each atom sits within the layers of the complex metal oxides that his lab group can create.

“It's pretty cool to see atoms,” Kumah said. “What blows my mind is that not only can we see where the atoms are located, but if they shift by even a trillionth of a meter, we can see that too.”

“What we find is that if you move atoms around by these really small amounts, without changing the composition, you can completely change materials from being good conductors of electricity to insulators, or from being good magnets to poor magnets,” Kumah said.

In his spare time, Kumah enjoys music, sports and baking. “Everything from macarons to cakes,” he said.

He’s also been learning to play the violin, an instrument he picked up for the first time alongside his daughter during the pandemic. During the COVID lockdown, he started studying by himself at home with YouTube, but now he meets an instructor once a week for lessons.

“We're going through Bach right now,” Kumah said. “I have to practice. I don't think I sound great, but it's a relaxing thing to do.”

In his 15-plus-year career Kumah has authored or co-authored more than 60 publications. He has been recognized with a 2018 CAREER Award from the National Science Foundation, and the 2022 Oxide Electronics Prize for Excellence in Research.

“I love teaching and research,” Kumah said. “One of the things I tell students is, with my job I wake up every day and I'm happy to go to work.”

Kumah lives with his wife and two daughters, ages 6 and 11, on the outskirts of Chapel Hill.